Radium was discovered in 1898 by Polish chemist Marie Sklodowska Curie. To produce radium, you need to extract it from pitchblende, an ore that contains uranium.

Radium was discovered in working with the known properties of pitchblende. Curie noticed that pitchblende in its unrefined state was more radioactive than the uranium that was separated from it. This lead her to correctly anticipate it containing additional radioactive properties.

Extracting radium is a complicated and involved process that requires a team of trained professionals. Extraction needs to be conducted at scale, due to only trace amounts being present in the ore it is extracted from.

After its discovery, scientists hailed it as a miracle element. Its unique properties came to represent modernity, industrialization, and technological advancement. The general public was quick to follow, and amplify this enthusiasm.

Radium girls

Radium’s most obvious property is its luminosity. It glows with a distinct, eerie green color. Readers of this post may be familiar with one of its more infamous uses: painting it on watches to create glow-in-the-dark dials.

Readers may also be familiar with Radium Girls. This deceptively cool-sounding name describes a working-class job that was highly desirable at the time. Radium’s technological applications afforded radium dial painters a salary that enabled a semblance of financial freedom. Radium’s public perception also gave the job a sense of glamor.

Radium girls were women who were coerced by their male superiors to meet the demands of society and technology. They were instructed to use their mouths to form a fine tip on the paintbrushes used to apply radium paint.

Over time, radium built up in these women’s bodies. This led to horrible injuries and tragic and extremely painful deaths. Before death, ulcers, lesions, sarcomas, the dissolving of tissue and honeycombing of bone occurred. The horrific symptom of a jaw rotting off occurred enough that the term “radium jaw” was coined.

The employers of radium girls initially tried to ignore, gaslight, and shift blame about the adverse effects of radium exposure, and their part in it. The United States Radium Corporation tried to blame Mollie Maggia’s death by radium poisoning on a misdiagnosis of syphilis. They then conspired to create a mass coverup to hide the ill-effects of working with the technology.

Productization

What is less known is how deeply integrated radium was into daily life. Radium was used a plot device in fiction, a beauty standard, even a topic for religious sermons.

Radium’s rarity made it a prestige good. Businesses were quick to take its initial applications and create a whole host of radium-themed products and branding—the more coveted ones actually containing the element. It was laterally integrated into nearly every existing product space: cigarettes, toothpaste, hair cream, butter, blankets, fertilizer, cosmetics, etc.

Radium’s integration also created a feedback loop that bolstered its credibility. This translated to its adoption by the medical community.

Doctors praised the supposed medicinal effects of radium without knowing its full effects, touting the rejuvenating powers of irradiated metal. Irradiated tablets were sold to the general public, to say nothing of radium-themed suppositories.

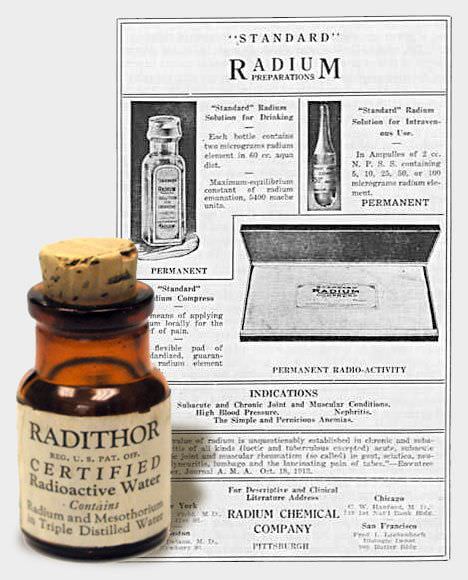

Perhaps the most infamous radium product was Radithor, a beverage created by Bailey Radium Laboratories. Radithor was marketed as an “elixir of life.” Unlike a lot of competing products in the radium beverage space, Radithor was a premium product that promised certified radioactive water.

Pittsburgh socialite Eben M. Byers died by compulsively over-consuming Radithor—his body was so radioactive that he needed to be buried in a lead coffin. Because of Byers’ social position, as well as coverage from the The Wall Street Journal, regulatory bodies were compelled to take action in banning its use.

What we can learn

There can be a lot of external forces that compel our technology choices, who we have implement them, and how they go about it. Unlike the prewar era, we now know a lot more about how technologies are built, how they work, and what their short and potential long-term effects are.

We should recognize the law of the instrument.

Blanket-applying radium to everything created horrific outcomes, some that we’re still being affected by today. Bottles of radium-infused beverages still show up in antique stores with some frequency. If they’re recognized as such, specialized containment and cleanup crews are brought in.

This being said, radium has some positive applications. Contemporary uses include treating some forms of cancer, checking machined metal parts for defects, and sourcing neutrons. These are situations where radium’s properties are purposefully and deliberately applied.

There’s a bit of nuance behind radium’s practical applications, as well: Many of its uses have been replaced by safer, more efficient innovations building off what it pioneered. The industries that use these technologies understand the importance of radium’s initial establishing role, but also utilize its successors.

Technology drives outcomes, but its selection doesn’t live in a vacuum. As technology workers, we have a responsibility to make careful and deliberate technology choices and not cause undue immediate or long-term harm.

A five page marketing website may not need a Single Page Application approach. Consider what you’re trying to do, how you’re going to do it, and how you treat the people that help you get there.