On September 17th, 1956 an atomic bomb was detonated in Maralinga, Australia.

The bomb’s testing program was codenamed One Tree, and utilized a payload comparable to the horrific Little Boy bomb dropped on Hiroshima, Japan during World War II. The test was part of Operation Buffalo, the United Kingdom’s anglophilic plan to use Australia as a location for nuclear weapon testing.

Maralinga was selected as a location for testing because of its remote location and desert climate. It was mistakenly believed that there was a low chance for collateral damage and witnesses.

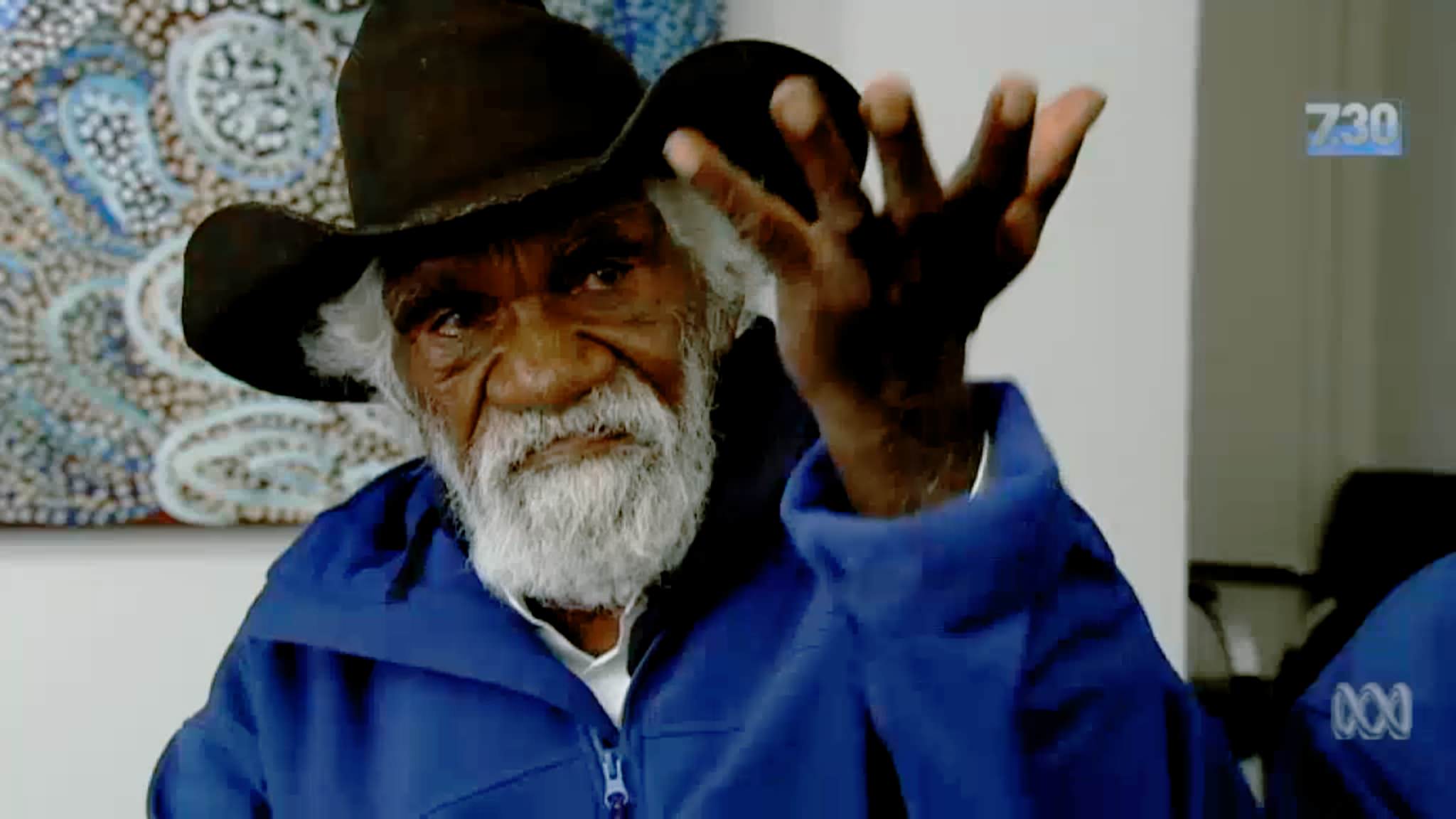

Nyarri Nyarri Morgan

Nyarri Nyarri Morgan is a Martu Aboriginal elder.

The day of the One Tree test, he was hunting on a trade route on their traditional lands, an area that included the Maralinga region.

Morgan bore witness to the One Tree detonation. In his own words:

We thought it was the spirit of our gods rising up to speak with us

A titanic fireball dominating the sky, followed by an impossible mushroom-shaped cloud and a shattering roar. This explosion was Morgan’s first contact with an outside White, Colonial culture.

Morgan’s life up to this point was so far divorced from this event that the lack of frame of reference borders on an experiential category mistake. Because of this, he did what any of us would do: attempt to map the alien experience to his existing framework for understanding the world.

then we saw the spirit had made all the kangaroos fall down on the ground as a gift to us of easy hunting, so we took those kangaroos and we ate them and people were sick and then the spirit left

The fallout from the One Tree detonation, as well as subsequent tests, caused untold, multigenerational harm to the Maralinga region and the Aboriginal communities living in it.

We all poisoned, in the heart, in the blood and other people that were much closer they didn’t live very long, they died, a whole lot of them.

First contact

Some Martu people did not encounter White people until the 1960s, but may have been ambiently aware of them from their ancestors’ experiences. Part of this avoidance stemmed from prior contact during the survey and creation of the Canning Stock Route.

Morgan had his first encounter with a White person, Len Beadell, in 1963. This was seven years after witnessing the atomic explosion.

An impossible gulf

To reiterate the experience: An Aboriginal man’s first encounter with a foreign culture was an atomic explosion. The first connection of that experience to the culture that created it occurred seven years after the event, seven years of invisible pain and death.

This is real, this happened. There is no way to emotionally understand the totality of this experience.

An attempt

Sydney-based immersive technology artist and director, Lynette Wallworth created Collisions, a 17-minute long virtual reality (VR) film that attempts to bridge this gap.

Collisions is an immersive experience that uses Nyarri Nyarri Morgan’s own words to describe the explosion, as well as Martu thoughts and practices on how to care for the environment. It uses the cutting-edge technology of 2016 as a vehicle to describe cutting-edge technology of 1956.

The hope is that the experience creates empathy for Morgan, as well as technology’s role in shepherding the future.

The limits of empathy

According to the Nielsen Norman Group, empathy is the ability to fully understand, mirror, then share another person’s expressions, needs, and motivations.

Empathy is currently a popular concept in the digital product creation space, the idea that it helps to create a closer connection to the people who will use the thing you make.

Empathy as a design practice—rather than an ability—also has problems. These issues are insidiously compounded by its prevalence in many inclusive spaces. Ivana McConnell does an excellent job of discussing this nuance in her post, Inclusive UX: The limits of empathy.

We need to make sure that those we’re aiming to help are not excluded from the process and that we solve the problem as they experience it, not as we think they experience it.

To call Nyarri Nyarri Morgan’s experience an extreme example of the limits of empathy would be an understatement. However, the story functions as an incredibly powerful learning tool.

Defining the extremes of something can be an effective way to discover its shape and identify areas where exclusion occurs. Because of this, it is a common Inclusive Design practice. However, there is some cautionary nuance embedded within this exercise.

Power

Defining an extreme runs afoul of the bias that the majority experience is default.

Collision’s premise extends in both directions. An Aboriginal man isolated from White, Colonial culture hunting in the desert would consider a post-nuclear age, post-Internet, VR goggle-wearing woman as unknowable as she would consider him.

Indecision should lead to representation, not tokenization

Empathy, and the implicit notion that it is intrinsically good, is not the answer. So how do you discuss something like this?

While I have not been able to personally experience Collisions, the research I have done on it tells me that Lynette Wallworth has intentionally crafted the experience so that Nyarri Nyarri Morgan is provided agency for the narrative he wants to communicate.

Collisions is not atrocity tourism.

The VR experience provides Morgan with mechanisms to communicate to a mainstream, contemporary audience his beliefs and perspectives, shaped by the blast, his cultural background, and his lived experiences both before and after the event.

Morgan’s experiences are not flattened or reduced. Instead of being tokenized, he is granted agency—the trauma of the experience is not re-inflicted on him as a gimmick.

If you are feeling indecision about where to go after reading through this, I’d encourage thinking about your relationship with empathy. Specifically, working through:

- The blurry line between empathy and sympathy as practice,

- How tokenization is conflated with representation, and

- How empathy is deployed in a professional context, and what power structures it upholds.

To paraphrase my friend Sam:

Design typically tells the story of how we think things are, frequently with stereotypes, which is what makes this work different. It’s in their words and not a caricature of the experience.

Decolonizing

It’s one thing to take a critical eye to things like personas, but it’s another to question the larger structures that facilitate and reinforce their use.

How have our histories and practices affected the way culture is manufactured? What decisions are being made for others without their input, or even awareness of their existence? What power structures inform our notions of frameworks, categorization, and cognition?

Representation is important, but it is also an output of a larger system. Decolonizing your practices is a good way to begin to unpack this system while being a participant within it.

Further reading

- Aboriginal man's story of Maralinga nuclear bomb survival told with virtual reality ABC News

- Maralinga: Sixty years on, the bomb tests remind us not to put security over safety ABC News

- Collisions Digital Dozen

- Maralinga: How British nuclear tests changed history forever Creative Spirits

- Landmark VR film reveals Indigenous encounter with atomic bomb testing Mashable

- Nyarri Nyarri Morgan: Virtual Reality, History and Indigenous Experience SoundCloud

- Inclusive UX: The limits of empathy Louder Than Ten

- The Limits of Empathy Harvard Business Review

- Thinking in Triplicate Medium

- What Does It Mean to Decolonize Design? AIGA Eye on Design

- Decolonizing Design decolonisingdesign.com

- The Politics of Design thepoliticsofdesign.com