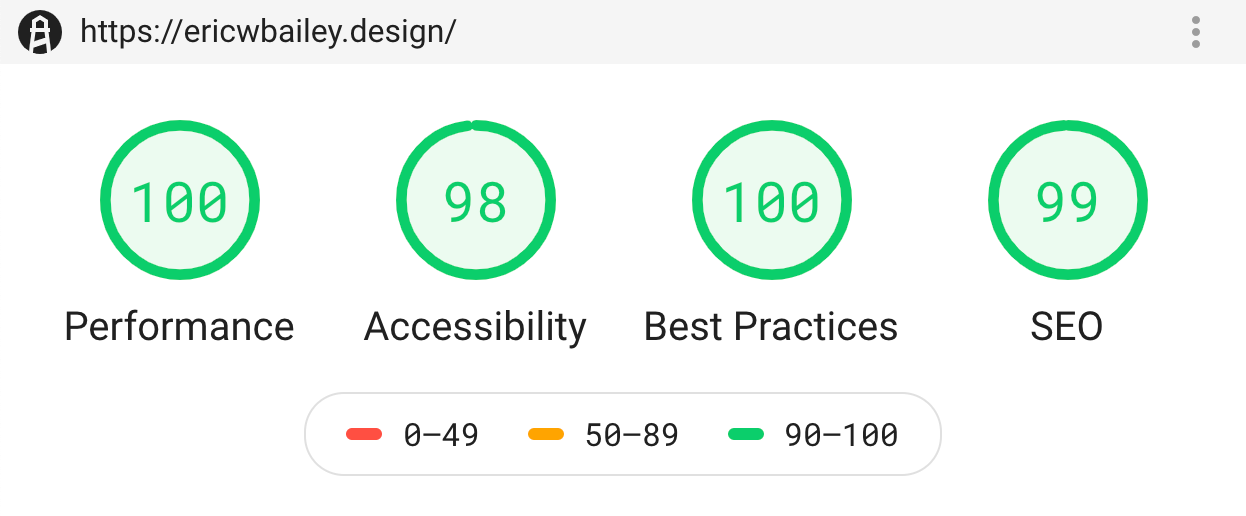

Lighthouse is an open source auditing tool made by Google to help developers understand how well their site is doing in terms of four metrics: Performance, Best Practices, Search Engine Optimization (SEO), and Accessibility. If you’re feeling adventurous, it will also measure your progress as a Progressive Web App (PWA).

These metrics are what Google uses to determine if you have a quality website or web app. Their codification means that we now have a relatively transparent ruleset we can compare our work against, instead of just making guesses and hoping their search ranking process likes it.

Search ranking is the name of the game. Google is, for better or worse, how most of us search for anything on the web now. Much like club bouncers, making ourselves look good for Google means there’s a better chance we get placed at the front of the line. And being at the front of the line is important—many businesses’ success lives or dies by it.

As far as metrics go, I think they’re great ones. The code it checks for covers a wide range of concerns, all of which compound to make your website or web app a far better experience from many different perspectives. I also think it’s a clever move on their part to quantify it visually. Getting those pie charts to display 100 is definitely an effective carrot for a lot of developers I know. Heck, it worked on me.

Moving the needle

Google will make adjustments to its search ranking process based on what it perceives as best for the people who use it. This behavior isn’t altruistic. It is a premeditated and calculated act to maximize its value as a product—people don’t have much of an incentive to use Google if the results it generates are poor.

Sometimes these adjustments are dramatic. In 2015, they introduced “#mobilegeddon,” a metric that penalizes non-responsive websites and web apps. It was a sensational update, but also a much-needed one, as it provided a huge incentive for companies to meet their customers where they were: on their mobile devices.

Another notable update was their 2018 Page Speed update, which penalizes the slowest, worst-performing websites. Again, this makes sense: if something is too big to load, takes too long to load, and/or costs you a fortune to load, there’s not a lot of incentive to visit it. A page that never loads can’t serve up ads, either.

Making Lighthouse happy makes Google happy, to a point

To the best of my knowledge, Google currently does not factor Lighthouse accessibility scores into how it determines search ranking. Unlike being non-responsive or non-performant, you’re not dinged for having an inaccessible site.

This is as curious as it is infuriating. The mechanisms that Google uses to comb through and rank website and web app content are analogous to how assistive technologies function. Wouldn’t they want to make this process easier for themselves? At the scale that Google operates at, faster and more accurate page scraping could translate to a great deal of money saved on computational power.

Switch it on

Here’s a thought: what if Google put its thumb on the scale again, only this time for accessibility? What if it treated the Lighthouse accessibility score as a first-class ranking metric?

Before we get too far down this path, I’d like to say this idea isn’t new, nor am I its originator. However, it does not mean the idea not worth discussing.

I’d also like to leave aside related points about Google’s monopoly on information access, it’s influence on the development of web technologies, as well as its push to popularize AMP in place of existing standards. They’re all things I’m aware of and concerned about, but beyond the scope of this post.

I am also aware that Deque’s axe API powers Lighthouse under the hood, why automated accessibility tests are only part of the picture when it comes to ensuring your site is accessible, and why a numerical score can be a fallacy in terms of guaranteeing actual usability.

The great de-rankening

We already know that nearly every major site on the internet is an inaccessible shitpile. Even if Google only penalized critical accessibility issues, there’d still be a drastic drop across the board. It’s such a pervasive problem that even Google’s own content would be affected.

This mass de-ranking would create fast and furious competition to regain lost standing—an event not without historical precedent.

Google Panda

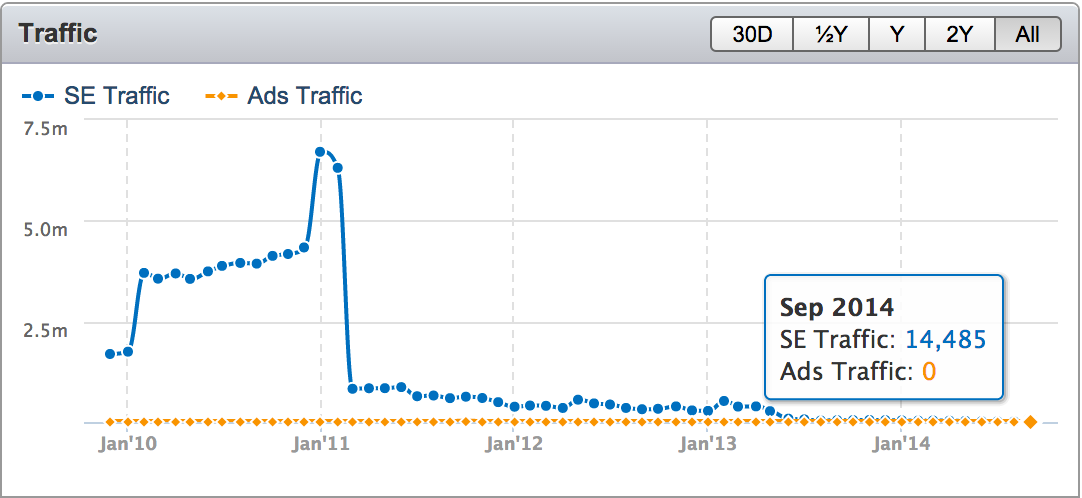

In 2011, Google began to make changes to the algorithms it uses to rank websites, to reward what it considered high-quality websites and punish the opposite. The update was known as Google Panda.

Google Panda specifically targeted a lot of unsavory SEO techniques, including content farms, “thin” content pages, low-quality affiliate linking schemes, and search query baiting. For those who made their living by gaming the system to serve up spam, it was disastrous. For those who just wanted to find what they were looking for online with minimal hassle, it was a huge win.

Blood in the water

Much like with Google Panda, there would be an inevitable scramble of activity to recover from the ranking hit for having an inaccessible site. With that scramble come the hucksters and the snake oil.

Accessibility work is difficult, accessibility remediation even more so. It’s easy to envision the rise of a cottage industry of people who promise quick-fix solutions to years of poor quality code. In fact, it’s something we’re already starting to see.

Plugins and overlays

Accessibility overlays are snippets of third party code you add to your website or web app. In exchange for some money, the service that maintains this code will generate a little modal window containing features intended to assist people with understanding and operating things. Much like a bandage left on for too long, this kind of solution inhibits growth and eventually causes what it covers to rot.

Because of their many, highly problematic issues, I won’t directly link to, or name any of the accessibility overlay products out there. However, I will stress my main concern: the simple fact that they don’t work.

The predatory exploitation of this space is disgusting. And, like any other third party script you add to your site, it’s code you can’t control. With that comes a gamble against issues surrounding trust, such as an (ironically inaccessible) text-to-speech plugin getting silently converted into a bitcoin miner.

I’d also be remiss if I didn’t mention how third party code can call in other third party code, including things like analytics and CRM tools. This capability is incredibly problematic with regards to disability, especially if it isn’t clear who has access to this information or what they’re doing with it.

Lawyers

There is now also legal precedent for individuals being able to sue private companies for having inaccessible websites (and rightly so). With that has come a rash of lawsuits created by ambulance-chasing lawyers, many who don’t have representation from an actual affected plaintiff.

Automated code checkers such as Lighthouse are a bit of a double-edged sword in this situation, in that you can just grab a list of the top one thousand websites, feed it to this sort of tool and have a list of potential targets ready to go in just a few minutes’ time.

My view here is the damage has already been done. These drive-by lawsuits create a bad impression of accessibility work to an industry that already has a dim view of it—better to scale it to the point where everyone is forced to put in at least nominal good faith efforts. Better yet, codify it into law and do away with the problem entirely.

Market forces

With the short-term problems acknowledged, I still think a mass de-ranking would make things better in the long run. For example, it’s easy to foresee a lot of effort finally getting directed into one of the areas where it’s needed most: code frameworks.

It would force these kinds of libraries to deliver on what they promise: quality code. After all, isn’t that why they exist? To lessen the amount of work it takes to make something, with the understanding that it’s built using community best practices?

You mustn't be afraid to dream a little bigger, darling

Gutenberg is inevitable. Third party plugins need to be bolted onto React to provide even a semblance of assistive technology-friendly navigation. Hang out on enough issue trackers, and you'll see a pattern of accessibility-related issues getting downplayed, deprioritized, and berated.

Frameworks are also here to stay—we’ll never get developers to stop reaching for them. To square this circle, maybe we force everyone’s hands and turn digital accessibility into the unavoidable, non-negotiable cost-of-entry consideration it should have always been.

Matt Cutts, Google's head of Webspam at the time of the Panda update, commented that “…with Panda, Google took a big enough revenue hit via some partners that Google actually needed to disclose Panda as a material impact on an earnings call. But I believe it was the right decision to launch Panda, both for the long-term trust of our users and for a better ecosystem for publishers.”

A better ecosystem is what I’m after. If that means having to petition the king, so be it.