I was kindly approached by Fable with an offer to evaluate their new pay-per-project model. It is a project-based option for accessibility practitioners, champions, and product teams that delivers quick feedback from disabled people who use assistive technology.

This service offering addresses a gap left by organizations and individuals who cannot use a more longterm subscription-based engagement. The idea behind this new model is to increase access to feedback from disabled, daily assistive technology users.

Pay-per-project targets:

- Larger organizations with longer procurement cycles,

- Agencies and consultants with variable-sized clients, as well as

- Startups and growing businesses who have to be strategic with budgets and resources.

I strongly believe in both:

- Making learning about accessibility more open, approachable, and affordable, as well as

- The direct representation from disabled people in all parts of the design and development process.

Given that, this partnership makes a ton of sense.

Don’t bury the lede

I got what I asked for, and it was amazing: Direct and actionable feedback from a diverse range of disabled people about their experiences using my website.

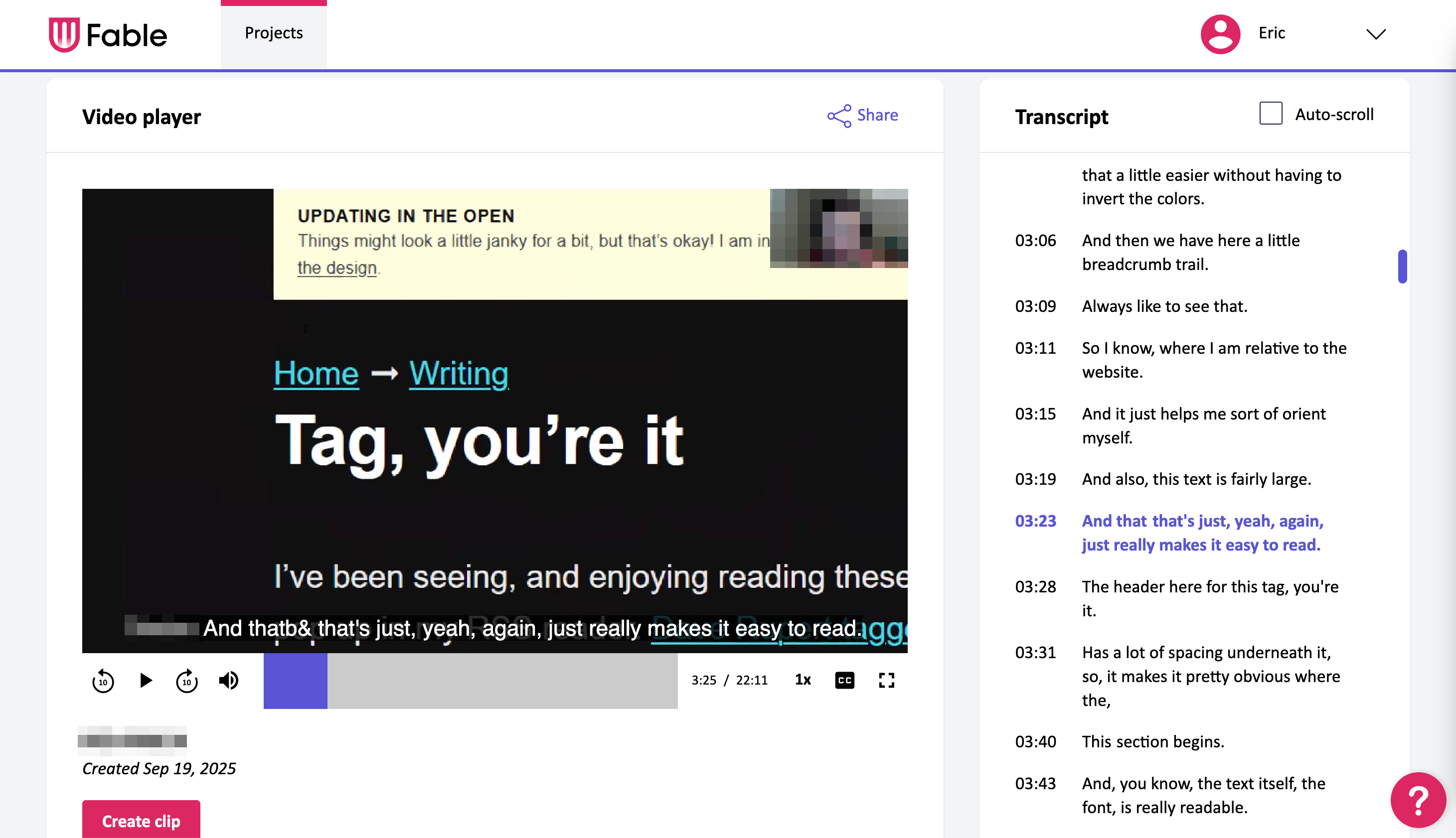

This feedback took the form of seven recorded videos. Each video captured a person navigating my website using assistive technology, while giving verbal feedback as part of the process. Each participant also rated the experience along a series of metrics, which in turn was used to generate a quantifiable usability metric.

These recorded videos reinforce the human aspect behind why we do accessibility work in the first place. This fact is hands-down the most important aspect of this service offering.

The feedback I received is going to be used to shape the next iteration of my site. It highlighted areas where I can directly improve the usability of things for multiple types of assistive technology.

I was comped by Fable for access to this service in exchange for writing this blog post. It cost ~$5,250 USD, which I feel is incredibly valuable based on what you get in return.

The setup

Acting on this new offering was a cinch. Signing up for Fable’s platform was simple and straightforward. Setting up a new project was, as well.

The process for creating a new project was broken into four steps, with clear instructions for each part of the process. I elected for a self-guided study, as I wanted to diminish the Hawthorne effect as much as possible.

I supplied the scenario for the study, which was:

I am in the process of redesigning my website. As part of this activity I would like input and feedback from disabled people to better understand what is and is not working with the current version.

I then supplied a URL for testing, which was a blog post on my site. I also:

- Included additional context to pretend like they stumbled across the link while reading a newsletter or browsing social media, and

- To note if they would realistically leave the site because of any encountered barriers or friction.

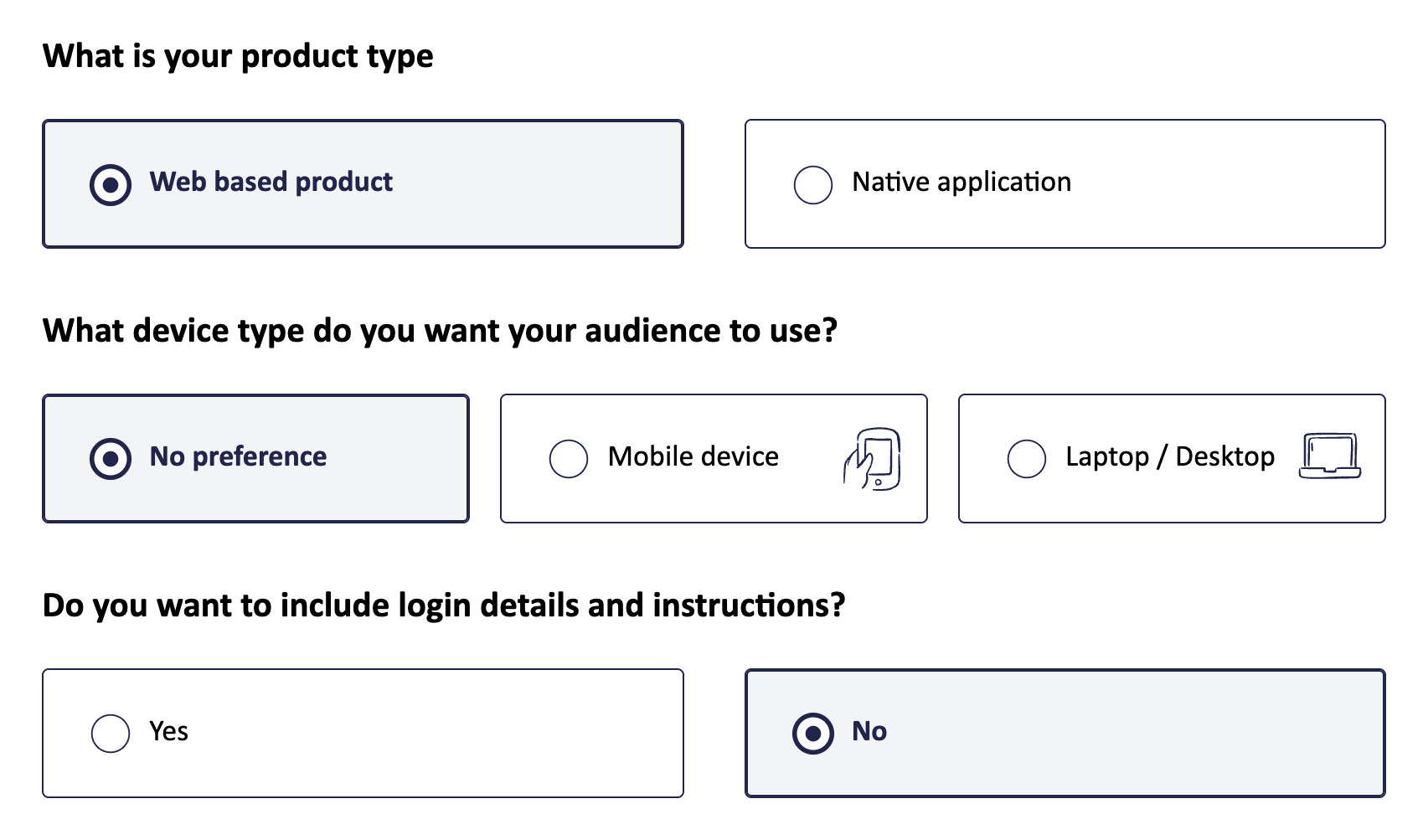

Fable also offered the ability to provide other qualifiers such as indicating if it was a web or a native app, as well as if there was a preference for only mobile or laptop/desktop devices to be used. I elected to not restrict this.

After filling out the required information I submitted the research request. Each request is reviewed by Fable, to help ensure the instructions are clear and actionable for their participants, and that the results I get are constructive and actionable.

Feedback comes in

Seven people in total provided feedback. There was representation from the following different types of assistive technology:

- Switch control,

- Voice control,

- Screen magnification, and

- Screen readers.

All participants elected to use a laptop or desktop, using both Windows and macOS as their chosen operating systems.

I was informed of each of the seven people’s individual completion of the study via notification emails sent to the email address I used to sign up. A final notification email was also sent to inform me that all participants had completed their evaluation.

All told, it took six business days for the requested task to be completed in full.

Each participant who marked their evaluation as complete has their own dedicated sub-page linked to from the project landing page. This page includes basic information about the participant, a video recording of their session, a transcript, and an AUS score.

As an aside, I’m a big fan of the AUS score. It’s a way to take something as highly variable and personal as a person’s own unique assistive technology setup and extrapolate it into a high-level understanding of your experience—both on a per-participant and aggregate basis.

The project landing page also supports the ability to generate reports that analyze information by a few different methods, including AUS score by assistive technology type, task flow completion, logged issues, etc. Additionally, it can display any clips you create when reviewing participant video.

All of this information and segmentation can be incredibly helpful for communicating with stakeholders. I find that reporting on metrics usually goes over better in our quant-obsessed culture.

That said, I’m team qualitative. Watching the videos as they rolled in was enthralling! I soon found myself looking forward to receiving the next notification email, ready and eager to take notes.

What I learned

The most important takeaway for me is a repeat of what I’ve voiced earlier: A reminder that all of this work is ultimately for people.

It can be easy to forget that people are the focus in the humdrum, day-to-day realities that make up a digital accessibility job:

- Auditing design and code,

- Creating and closing tickets,

- Debating WCAG particulars,

- Defining severity levels,

- Looking at coverage statistics, as well as

- All sorts of other dry and impersonal concerns.

This minutiae can all conspire to distract you. Watching the videos and hearing feedback breaks that distraction, brings you out of this abstract mode of thinking, and re-grounds you in why accessibility is so important.

I found myself grinning in delight alongside one participant who was listening to some lovingly-crafted alt text I wrote. I also found myself frustrated alongside another participant who found a bug with how I declared aria-current on some navigation.

Having a direct line to these experiences is nothing short of compelling, and something I urge you to also try

Themes and takeaways

What I specifically took away as things to improve could be a blog post unto itself. To spare you that, here’s a list of some of the more significant findings that stood out to me:

- Distinct active states are important for a few different interaction approaches. I noticed that people who have low vision, and who use keyboard emulators and alternatives such as switch and voice control especially appreciated active states when present. This is because it served as extra reinforcement that the action they requested was successfully undertaken.

- Having your color theme automatically default to whatever theme someone’s operating system is set to use is huge. Multiple participants voiced appreciating that it spared them pain or discomfort in that they didn’t have to struggle to find the website’s theme toggle, or use an operating system feature to force a color inversion.

- Repeating primary navigation at the top and bottom of the design is helpful and expected. My site currently places its primary navigation at the footer, in the idea that it’d subtly nudge people towards reading the main content. This worked against me in that people were curious or confused about how to get around when first scanning the page.

- Font choice matters. Multiple participants commented on the distinct type, as well as its contrast against the background color. One participant specifically called out appreciating the difference between the “o” and “a” glyphs.

- Proximity and predictability matters. Multiple participants also mentioned appreciating that there was sufficient space between paragraphs and headings, but also not too much space. Additionally, the predictability of type size and spacing not changing too much in different areas of the site was also called out.

- Single columns of content make it easier for a variety of assistive technologies to navigate and read. There is just net less guesswork to figure out if you’re missing something or not.

- Figure captions are valid HTML, but many people got tripped up on the caption content itself. I think this one is on account of it being less commonplace on the web.

Reminders

Another aspect of working on the web day-in and day-out is that you become surrounded with people who think, talk about, and operate things the way that you do. This applies for both regular web design and development, as well as digital accessibility as a focus area.

Watching these videos reminded me that for most people, the web is a means and not an end.

- Some people didn’t understand where my website ended, and another’s began.

- Others internalized bugs with their assistive tech, operating system, and browser as their own failures.

- Some people got hung up on jargon.

- A few requested features that exist within the browser or operating system as native functionality, whose existence may not be easy to discover.

This is entirely understandable, and well-worth being made aware of again and again.

Via the lens of being a means, your web experience is nothing more than something that connects someone to what they want. It should support a person making said connection with as little friction as possible for whatever way they use technology in any given moment.

Another reminder is that individuals tend to give feedback based on their immediate wants, needs, and desires.

- Some expected functionality that isn’t native to the web experience.

- A few requested features that would have made the experience less easy to navigate for other forms of disability.

Both of these pieces of feedback make sense in remembering that disability is not a monolith.

Synthesis and power

I have background in both user research and digital accessibility. I also understand that inclusive user research is not the same as “traditional” user research.

Because of this, it is easier for me to separate what issues are WCAG violations from what are more subjective irritations. I’m also familiar with what feature requests might be detrimental to other forms of assistive technology.

That established, I still worry about my own conscious and unconscious biases when synthesizing the feedback I received. I’m also cognizant that I have a lot of personal feelings tied up in my own website.

This knowledge can be helpful, in that it energizes me to make changes to things that aren’t working. It can also be a detractor, in that I might unconsciously be less inclined to address things that don’t align with my own personal preferences and understandings.

With this established, I wonder what other people who use Fable’s pay-per-project model will do with their findings. This applies to people who don’t have the background I do, and even moreso applies to the audience Fable is targeting with this service.

Individuals and smaller organizations may be more passionate and mission-driven than larger organizations. Think nonprofits and startups. They may also have less experience or infrastructure in place to deal with this kind of content—doubly so given how rare disability-led resources are.

Because of this, I worry about how people who commission the study will respond to the feedback they receive without the benefit of a professional performing synthesis for them.

I’ve witnessed organizations doing things like over-correcting for one person’s access needs at the expense of others. Part and parcel with this are other phenomena like treating one person’s feedback as gospel, or never returning to re-investigate things further.

I’d also be remiss if I didn’t warn against turning this kind of feedback into a persona. I’d also hate to see folks jam transcripts into a LLM for this sort of thing, as well.

Opportunity

Part of my concerns about misuse of feedback are offset by resources Fable offers, namely:

- Non-metered tech support to help interpret findings,

- A blog,

- A comprehensive assistive technology glossary, and

- A focused training product offering.

With these resources considered, I also wonder if Fable could also provide an option for light synthesis as part of this service offering. I could easily see it being an upsell opportunity, as well.

UX research is specialized and painstaking work. Doubly so if it’s inclusive user research. I don’t want to devalue this expertise, but I also wonder if there is a way to better equip the person using the service for success without breaking the bank.

That said

Fable’s pay-per-project is a gift.

It is an opportunity to get valuable insight about how your digital experience works for disabled people. This is combined with dedicated tools to help communicate these findings with your organization.

Identifying areas where there are insurmountable barriers does not require specialized training. All it takes is a willingness to be open to improving your experience, as well as some patience to watch the feedback you receive.

Inclusive user research should be part of everyone’s product strategy

Disability-centric offerings geared towards improving digital products has historically not been a thing up until recently. Fable changed that with offerings such as the Accessible Usability Scale, usability studies, and Fable Upskill, a training product for digital product teams.

I’m heartened to see Fable making it easier and more affordable for organizations to include feedback and perspectives from disabled users with their pay-per-project offering. Here’s to a more inclusive and accessible web!