Slack went from IRC-but-with-WebKit to critical piece of business infrastructure almost overnight. I’m a big fan. It freed us from the tyranny of passive aggressive email chains, and when practiced with good etiquette quickly became my favorite way of communicating via text at work (and also not at work).

Critical business infrastructure is the interesting bit. All sorts of information accumulate as an organization continues to use Slack: favorited messages, screenshots, shared files, private channels, DMed passwords, application access, etc.

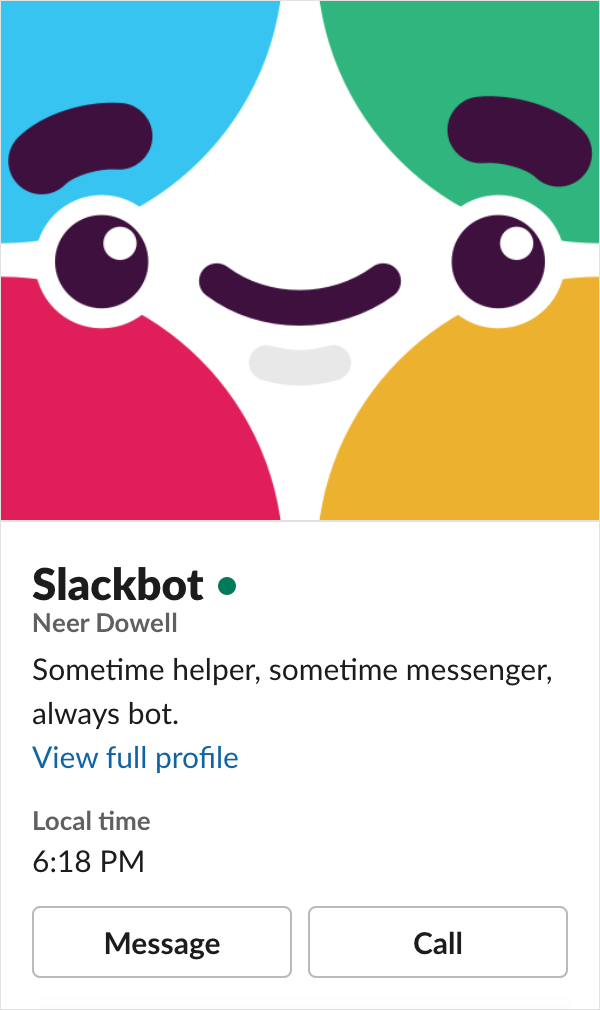

Slackbot

Slackbot is Slack’s voice of the system. It’s the first thing you interact with when you log in, the presence that tells you about reminders and tasks you set, and the way Slack uses to communicate platform-level issues and concerns.

Representing yourself

Slack is also permissive in terms of how you present yourself as a person who uses their app. This is, generally-speaking, a good thing!

Names

You have two different names on Slack, your full name and your display name.

Your full name is a name you can chose for yourself. People often use it for nicknames, or to do things like list their pronouns or status (i.e. “Katrina Santos [On Vacation]”). Your display name is oftentimes set by the organization running the Slack, and is used to @mention you.

A good way to think about these two name types is your display name is like your email address, and your full name is like the name you use with that account.

Your Slack full and display names can be a single character, or use non-English languages—a breath of fresh air compared to systems with Western biases that don’t accept things like diacritics or two-letter names. You can even use a DROP_TABLE statement for your name, and it’s smart enough to sanitize the input and avoid a little Bobby tables scenario.

Avatars

You can use whatever photo or illustration you like as your avatar. This is great! I use an illustration for some Slacks I participate in, to match the illustration I use on social media. In more professional contexts I use an actual photo of myself:

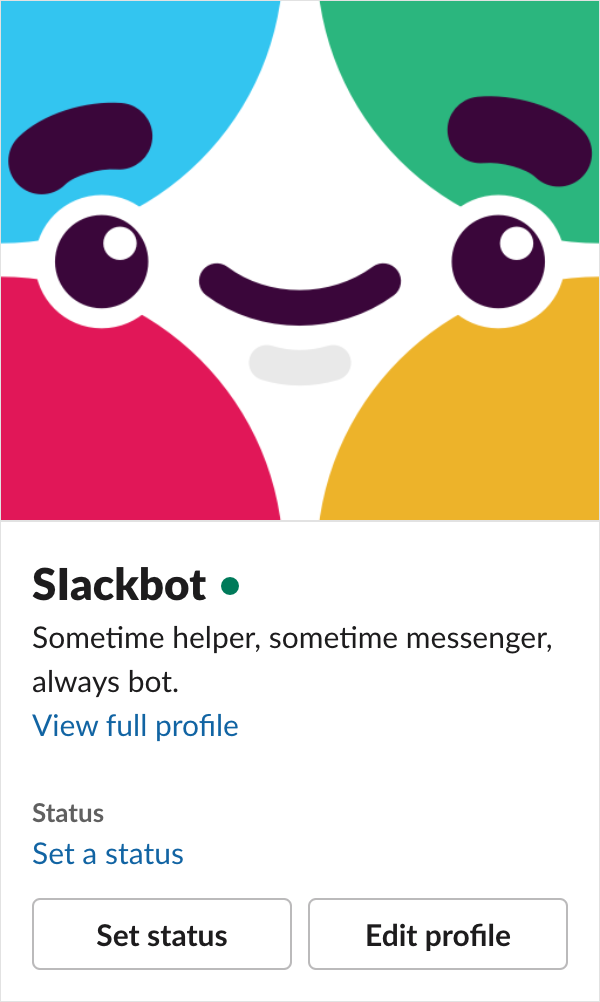

Misrepresenting yourself

Unfortunately, this flexibility can work against an organization. To cut to the chase, you can change your full name and avatar to pretend to be Slackbot:

Now before you start drafting a response, know I’m aware of these four things:

- You can view a full profile to see someone’s display name, and that they’re pretending to be Slackbot,

- @mentioning someone’s display name can also reveal the truth of things,

- Slackbot conditionally displays a tiny, unique heart icon when you view its profile, and

- Slackbot’s profile actions differ from a human’ profile actions.

Now know the scenario I’m about to describe creates an environment where someone is not likely to try to check these things.

Spear phishing

If you are unfamiliar, spear phishing is a technique where someone acting with malicious intent identifies a specific target or targets within an organization in order to get access to their information, and the information of the systems they have access to.

Unlike the shotgun blast that is a regular phishing attack, spear phishing requires a certain amount of social engineering.

Perusing an organization’s about us or board or directors pages, public-facing org chart, LinkedIn, or annual reports is a good way to start collecting targets. You could also take the slow boil approach: target someone lower in the organizational hierarchy, see what they've got access to, and work your way in and up from there.

For our purposes, we’ll need to identify important people with both a high degree of importance but with a low degree of tech literacy, i.e. your average white, male C-level executive.

Create a problem, then offer a solution

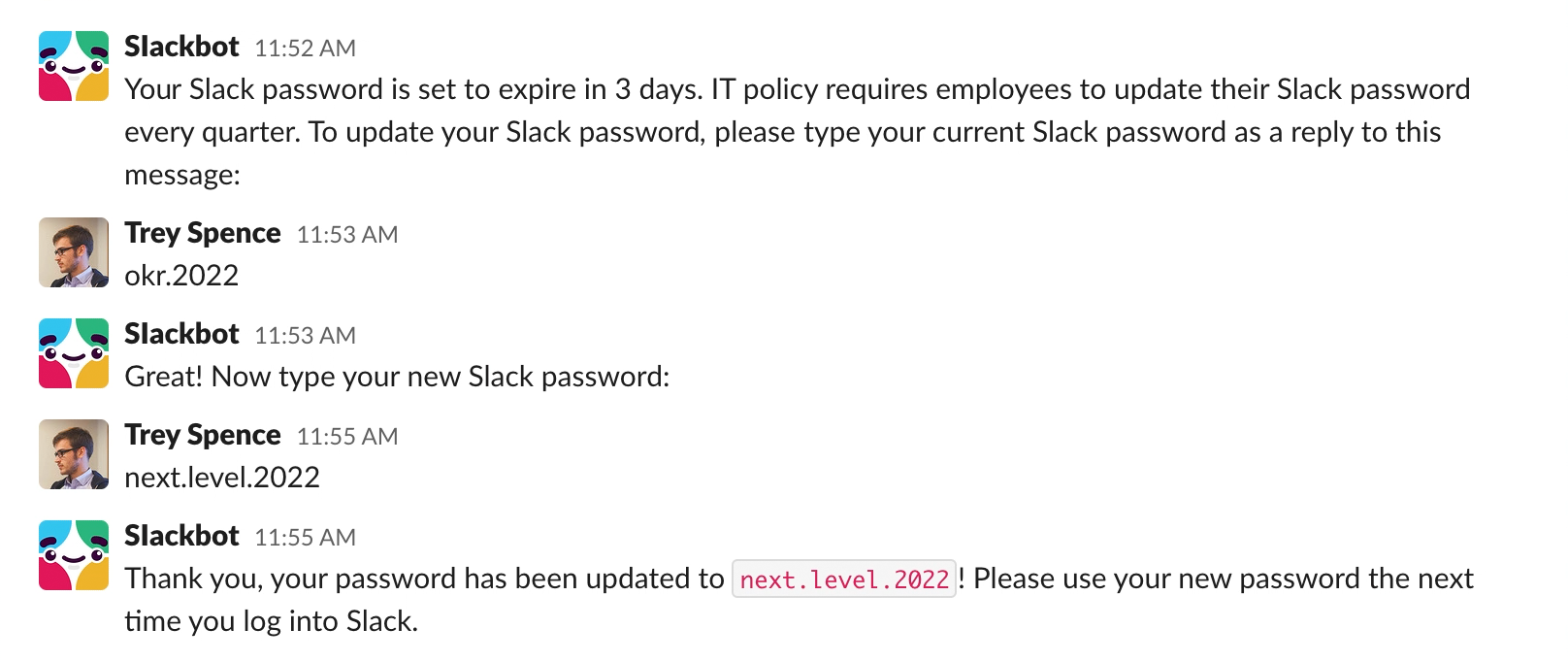

To keep someone from being skeptical, we’ll want to put them in a panicky state where they’re focusing on the immediate problem. Then, offer an easy way out of it. To do that, we stir up a little panic:

Offering to update their password provides an immediate solution to the problem at hand. The convenience of the solution we offer may outweigh that vital moment where they’d check to see if it’s legit. On top of that, we’re borrowing the look and language of Slack to reinforce a sense of automated authority.

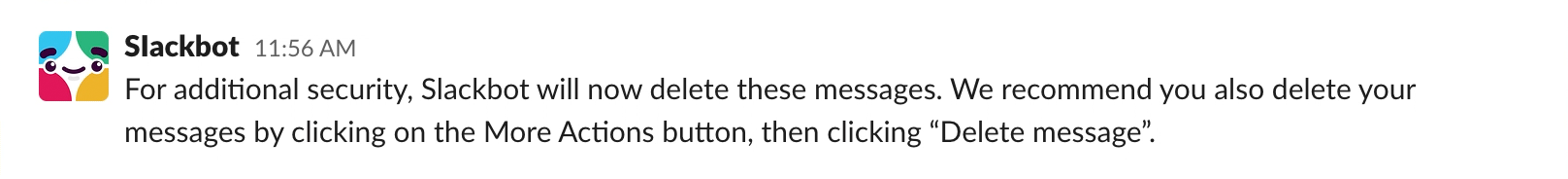

To extra mile it, make covering your tracks look intentional:

Now what?

We now have our target’s Slack password, which lets us access anything in Slack they have access to. A lot of people don’t use unique passwords, so we could also try logging into other services to see what works.

If your attempt doesn’t work, you can always claim you were part of a security training initiative, thank your target to make them feel good about themselves, and wait to try again with someone else.

Won't this get you fired?

A thing companies must contend with is the idea that applicants are trying to get access, not get a career. Corporate espionage is very real.

In addition, The Great Resignation has made it a job-seeker’s market, one where I’m willing to bet a lot of applications are rushed through and a lot of internal vetting processes have deteriorated (HR folks are also quitting en-masse).

What about non-work Slacks?

They exist, and many of them have hundreds, if not thousands of members. This is another tempting target if you do a little homework beforehand.

What Slack can do about it

A few things!

Show the display name on a profile preview

Make this information one level deep, not two. I can understand that there’s a lot of competing priorities for this piece of UI, but I think it’s a relatively easy lift that could do a lot of good.

This isn’t enough, however. The green online dot status indicator ( ) looks too similar to Slackbot’s heart icon (

) looks too similar to Slackbot’s heart icon ( ), the full name is small, and the discrepancies in different profile actions could be easily lost on someone. We can do more.

), the full name is small, and the discrepancies in different profile actions could be easily lost on someone. We can do more.

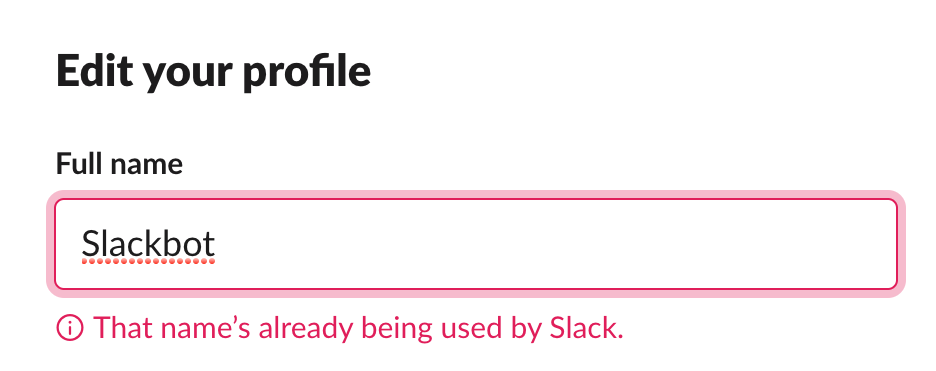

Prevent people from using “Slackbot” as their full name

Slack currently prevents you from using “Slackbot” as a full or display name:

It doesn’t, however, prevent people from being sneaky:

Full and display name logic could check for sneaky permutations of the name, ones that include foreign language glyphs that visually look like English letter glyphs, that sort of thing.

Cynically, I'd also wager names like “Slackbot.” or “S|ackbot” might even be enough to fool some people.

Prevent people from using Slackbot’s “What I do” text as their own

This is the same idea as disallowing people to use “Slackbot” as their full name. Preventing people from using the text, “Sometime helper, sometime messenger, always bot.” will remove another way someone can try and trick someone into believing they’re Slackbot.

Check to see if the uploaded image uses the same file name as Slackbot’s

I was able to snag a copy of Slackbot’s avatar by right clicking on it in the browser version of Slack. Slack could add a little more intentional friction by checking to see if the file name of an uploaded avatar image matches what is currently being used for Slackbot, and block it.

Friction is the key word here. It probably won’t stop someone from renaming the uploaded file, but it does signal Slack is aware of what they’re trying to do.

Hash Slackbot’s avatar image

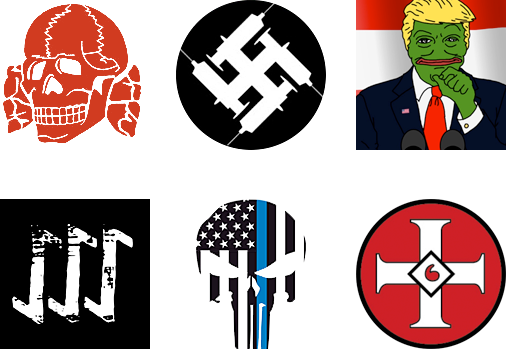

Image hashing is the practice of using an algorithm to identify an image—a technique used to check to see if an image is a direct or close enough match to another image. This technology is commonly used to detect copyrighted material, disinformation memes, and child pornography.

Slack could use image hashing to detect someone trying to use Slackbot’s avatar—or a slightly modified version of the Slackbot avatar—as their own. It could then prevent it from happening.

Verify perceptual hashes match modified Slackbot avatars

Trust, but verify, as the saying goes. We’ll want to test a range of modifications to Slackbot’s avatar that look official enough, but could try to get around image hashing checks:

Visual hashing may also not be enough. Machine learning may be able to help in situations where images that look like Slackbot’s avatar have been modified enough that they may not trigger hashed image detection.

Take it a step further

Image hashing and machine learning could, hypothetically, also prevent the use of common hate symbols as avatars. The Anti-Defamation League painstakingly collects and categorizes many of these images, which would could make for a good starting point.

Discord could also borrow this idea. Tech isn't neutral and hate organizes on platforms like these.

Solutioneering

It’s easy to be an armchair critic and point out potential solutions to problems you create. It’s another thing entirely to institute these kinds of fixes for a product already in motion, especially for one as complicated and popular as Slack.

The reality is these features will need to compete with multiple existing initiatives, as well as the practical and ethical mindsets of the people working on these platforms.

Some may think this is all paranoid delusion, some may run cost-benefit analysis and decide it’s an acceptable risk, and some might even be actively exploiting such a technique for their own gain.

For harboring hate groups, the other cynical reality is that many organizations are already aware of the issue, but are unwilling to remove a source of profit. Twitter, for example, flags many accounts that would violate German hate laws, but choses to display them to non-German accounts rather than removing them from its service.

Oftentimes, unfortunately, the most effective way to institute a fix for this sort of thing is after the abstract becomes real, the damage is done, and legal action is brought to bear.

Be the villain

We need to think like monsters in order to prevent harm. By facilitating difficult conversations about how features can be misused, we can reduce the damage our products create.

I have a talk that explores this area of product design, as well as strategies for how to approach it. If this is something your organization is interested in please reach out.