For better or worse, I spend a decent amount of time on social media.

When you read it regularly, you start to notice that there’s an ebb and flow to the kinds of things that get brought up. People post ideas and observations, followed by reactions, counter-reactions, meta-reactions, subtweets, side and backchannel conversations, etc.

One observation, “The term ‘a11y’ isn’t very accessible.” seems to pop up like clockwork. Most of the time, I bite my tongue when I see this surface-level remark and move on.

However, it seems like I stumble across popular web personalities making this observation with increasing frequency. Maybe it’s due to the increased attention accessibility is getting in the design and development spaces. Or maybe it’s due to the filter bubble of who I follow on social media. Regardless, it does seem to be compounding to the point where it compelled me to take action.

What is a11y?

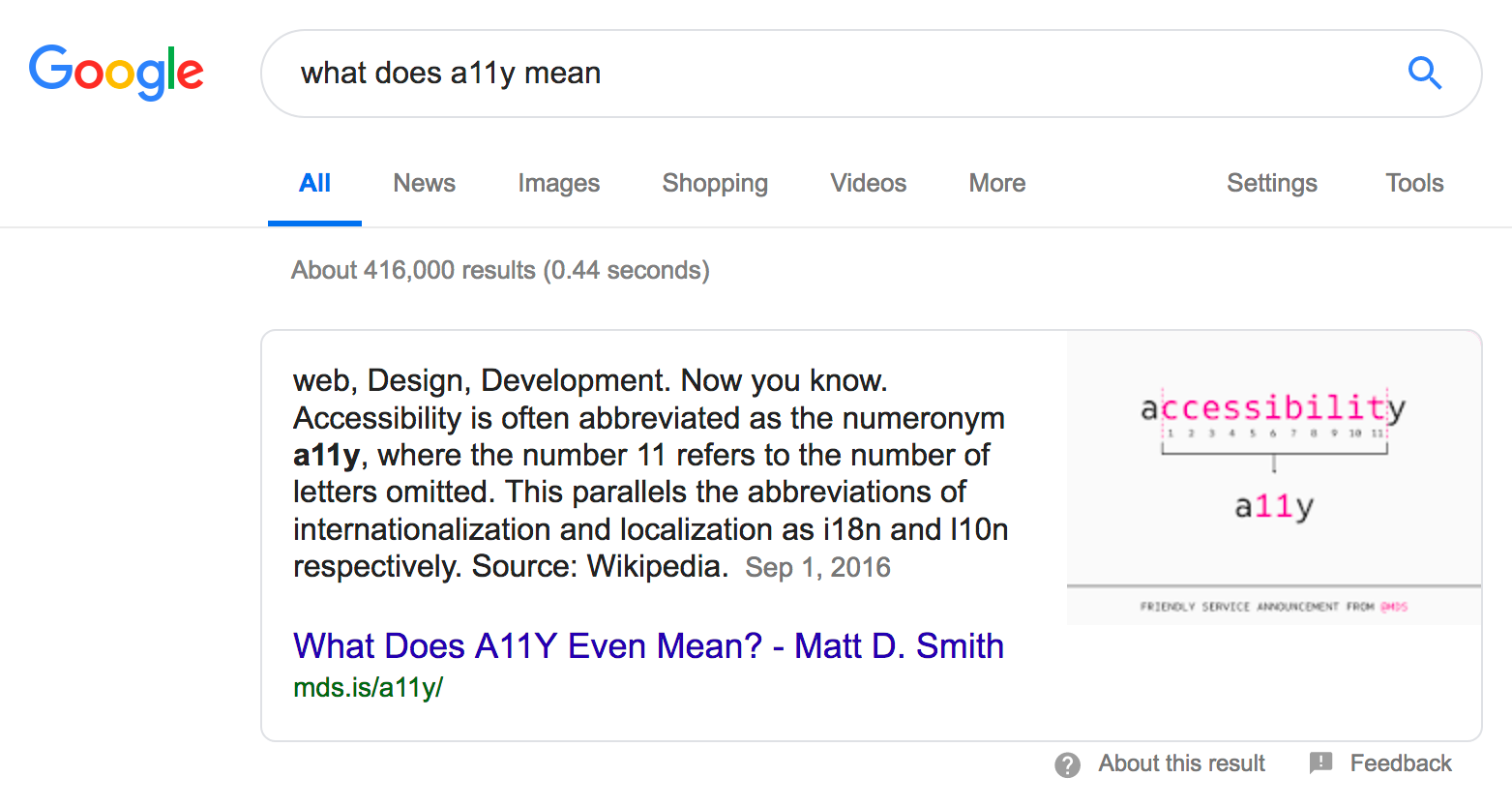

First off, we need to establish what a11y is. It is a numeronym that stands for “accessibility.” This isn’t that difficult a thing to figure out—a quick Google search gives us the answers we need. You might not even have to leave your search results page to learn its meaning:

Numeronyms aren’t new, nor are they something foreign to the industry. To name a few:

- 911

- 3D

- d11n

- P2P

- Y2K

- K-9

- l10n

- 411

- i18n

- .45

- WWII

- G8

- 401(k)

- 101

- MST3K

- W3C

- S3

How many of these terms are you already familiar with? I’m willing to bet a decent amount.

Origins

I don’t know the first person to use the phrase “a11y”, but Twitter’s original character count can be attributed to popularizing it.

Originally used by accessibility practitioners to save on character count when talking shop, it was further codified as a hashtag when Twitter decided to natively implement a feature that was formed from emergent user behavior—a surprisingly uncharacteristic move for the platform.

As the tweet length on Twitter was expanded to a luxurious 240 characters, the hashtag stayed on, serving as either a way to continue to save characters, or as a categorical marker to flag tweet content for others.

Purpose

Thanks to the English language’s adaptable nature, different words can have different connotations depending on the overall context of the sentence they’re placed in. In the context of the categorical marker, a11y serves as disambiguation, the process of making something more clear.

If I search Twitter for a11y, my results are more focused than if I search for accessibility. I’m not getting results for courses that make foreign languages more approachable, or how access to public libraries makes research results more rich. I’m not even seeing as much content that deals with accessibility, but at a too high or generalized level.

a11y neatly sidesteps this issue, which is why we can see examples of its usage outside of Twitter:

- Rob Dodson’s fantastic A11ycasts series, which carries Google’s stamp of approval and currently clocks in at ~90,000 views.

- Pa11y and Sa11y, suites of automated accessibility testing services.

- A worldwide network of conferences, webinars, and meetups attended by thousands of people, including a11yTOConf, Buffa11y, A11Y Talks, A11yNYC, a11yscotland, a11ylondon, A11yBH, and A11y Meetup Berlin, to name a few.

- A number of podcasts and podcast episodes, including A11Y Rules, the a11y Cocktail episode of Front End Happy Hour, and the A11y is your ally episode of JS Party.

- David A. Kennedy’s excellent A11yWeekly newsletter.

- Carie Fisher’s A11Y Cats, and other accessibility-themed merchandise.

- The A11Y Project, a website I proudly help maintain.

- etc.

We don’t use the red dot of light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation to harass our cats. Nor do we check what radio direction and ranging has to say about the day’s weather forecast. When I’m on vacation, I don’t look at tropical fish with the help of a self-contained underwater breathing apparatus. Those tools are lasers, radar, and scuba, three acronyms whose use has become so ubiquitous that they’ve become common nouns.

I never see people asking why WWI is written out the way it is, either. Won’t people confuse that with the first Wonder Woman movie? Or the first season of Westworld? Or some new Weight Watchers product? I also never see people questioning technical numeronyms like P2P, S3, or W3C?

So why do people focus on a11y?

Ableism

The easy answer is a quick joke about a perceived irony. A more complicated one is internalized ableism.

To quote the Center for Disability Rights, ableism is “a set of beliefs or practices that devalue and discriminate against people with physical, intellectual, or psychiatric disabilities and often rests on the assumption that disabled people need to be ‘fixed’ in one form or the other.”

It’s a pervasive problem, one that’s been normalized in our discourse to the point where it’s almost invisible. Think about the last time you called something or someone, “lame,” “stupid,” “crazy,” “retarded,” or “idiotic.”

Employing more effective adjectives is great. However, removing abelist language, practices, and thoughts involves listening to individuals who are willing to spend the physical and emotional labor to tell you what needs to be reevaluated.

Thanks to the internet, that kind of information can be discovered quickly and easily, provided you know the issue exists (oh, if only there was a hashtag to help us).

Onus

I’m nearsighted. I get migraines from time to time, as well as deal with bouts of anxiety and depression. But all things considered, I am an abled, straight, white, cisgender man. So why am I the one telling you all this?

As alluded to earlier, it is not the responsibility of a minoritized group to explain itself to you. Even if these types of questions and observations are asked in entirely good faith, it’s still a Sisyphean task that places a disproportionate burden on the person responding. This isn’t great for any group, especially one that created Spoon theory.

It’s also a common abuse tactic online, where the aggressor asks someone to explain themselves in bad faith, betting on them expending time and effort. Thanks to the problem of other minds, you can never know the intentions on the other end of the conversation.

But I’m a good person!

You may be thinking this after reading the previous section. And you know what? You probably are. I do think most people strive to do their best.

If reading about Abelism made you feel uncomfortable, that’s probably a signal that your worldview, and therefore your sense of self are being challenged. And if you made it to this part of the post, great! Sit with your discomfort for a bit and question why you feel this way.

I’m willing to bet that a non-trivial amount of readers skipped down to the next section, or more realistically, closed the tab when their cognitive dissonance flared as their mental models were challenged.

When you say, “The term a11y isn’t very accessible.” are you actually saying that a term that discusses disability needs fixing?

Subconsciously or consciously, the mental models that construct our world-views can, and do affect and infringe on others. Setting aside situational attribution for a moment, we need to unpack what “good” is, in the scope of perceiving yourself to be as close to perfect as possible for what society demands of you.

The thing is: perfect is static, but the world is dynamic. Participating in culture means constantly reevaluating your position in it, and how it affects and is affected by others (see the emergence of identity-first language). This takes work. But consider the alternative.

So much of our language is ableist or othering, and we don't realize it. I see language in accessibility audits like "the screen reader user", or even heard someone say "these people" when referring to disabled folks in a conference talk about accessibility. #a11y — Nicolas Steenhout (@vavroom) June 6, 2019

Allyship

Allyship is the “active, consistent, and arduous practice of unlearning and re-evaluating, in which a person in a position of privilege and power seeks to operate in solidarity with a marginalized group.”

You can’t be “the best ally.” It’s not a state to achieve, a switch that’s flipped, a system to rank up in, or a line item on your résumé. Importantly, it’s not a status you can lord over someone else.

Allyship is an ongoing process where trust, education, and accountability are built with minoritized groups. It takes hard work, but it is well worth the time spent.

It’s also worth saying that I’m still working at combating my own conscious and unconscious biases and prejudices, especially ones concerning disabilities. I am constantly learning and re-learning about this space, and I am fortunate to be welcomed into it.

That being said, a11y is a term created by the web worker community and organically adopted by, and rallied behind by its practitioners—both disabled and abled.

There’s a part of me that feels incredibly uncomfortable writing this post. I write and speak a lot about disability and inclusion, but I do not speak for the group or try to be its savior. To that point, I’ve been trying to incorporate more disabled voices in my work. I don’t want to dominate the conversation, nor force others out who should be present.

I also want to avoid tone policing. This one is easy: Some disabled people don’t like the term. In this case, you don’t push them to explain their position. Modify your language and behavior to accommodate their stated preference, and feel grateful that they cared enough to tell you. Easy.

Criticisms

I should also do my due diligence pointing out some other issues with the term a11y. Most of them have been brought up by others, but they’re worth resurfacing here.

Legibility

The term “a11y” looks a lot like the word “ally.” Intentional? Perhaps. Beneficial? I think so.

If you are concerned there will confusion over what the term will be interpreted as when read, that’s a problem with your typography. If you are empowered to, take the time to update it to be more accessible.

Spell checkers

Some dictionaries will flag a11y as a misspelled word. They’ll also probably flag many other terms, technical and otherwise. That doesn’t mean they’re not words.

This topic is a whole post unto itself, but it may be worth thinking about where the words for these dictionaries are sourced, and how they contribute to how we communicate.

It’s awkward to type

If you’re using a software keyboard, switching between alphabetical and numerical keyboards takes effort. This could be especially problematic if you have a motor control disability. However, it’s still less keypresses than typing “accessibility” out in full (6 versus 13 on iOS). Also, when typed enough, many software keyboards will add it to their dictionaries for autocompletion purposes.

Furthermore, “accessibility” is a long, multisyllabic word. That can make it problematic to read or spell out, especially for people with cognitive concerns.

Screen readers

Some people mention that “a11y” may not be pronounced as expected in a screen reader or narrator? To which I say: that’s exactly the point.

A screen reader reads the screen the way the person using it has instructed it to. You don’t want to try and overwrite its verbosity and pronunciation settings, as you’d be disrupting someone’s explicit preferences and expectations. Doing so also indirectly communicates that you think that the way they interact with technology is invalid.

I've had web devs ask me if they can control what the screen reader says or which voice or speed it is said in. I said no, and that's a good thing. All that would achieve is that your users would hate you. https://t.co/UsuAB3Zajv — Geoff Shang (@GShang) August 9, 2020

How do I use it?

Like a lot of accessibility work, knowing how, when, and why to use the term largely depends on being conscientious of context. It’s also good writing practice.

Many professions require good communication, and therefore good writing. Copywriters, user researchers, designers, developers, project managers, translators and localizers, marketers, etc, should all be conscious of their audience; their level of experience, their reading level, their areas of expertise, etc.

For me, a11y is largely a categorical marker. Like a signal flare, I’ll append it to tweets when I want to increase the chances of the content being noticed outside of my immediate followers.

Like any other abbreviation, I observe the Web Content Accessibility Guideline’s (WCAG) Success Criterion 3.1.4. Like any other acronym or industry jargon, I spell out the term in full the first time it appears in my writing, then follow it up with the acronym it represents:

Accessibility (<abbr>a11y</abbr>)

As it is industry jargon, I try to be aware of the context and known level of cognition my writing will ultimately wind up in. If it is for peers, the term might be used casually, alongside other jargon like AT, DOM, AA, JSON, etc.

How do I not use it?

If it’s for an audience who is new to working on the web, including learning about accessibility, I will probably not use the term until they feel more acquainted with the space.

I also don’t try to slap it in to replace the term “accessibility.” Sentences like, “Make the best a11y on your website with these 5 tips” feel forced and artificial.

a11y is here to stay

The genie is out of the bottle. The ship has sailed. The egg is scrambled.

If you’re a popular personality on social media, it’s worth some self-reflection about the ripple effect of making this observation about a11y’s perceived obtuseness.

By leaping to score some quick clever points, you’re also signaling that some negative behaviors are acceptable to model: namely gatekeeping, scapegoating, and most importantly, denying the self-disclosed identity and viewpoints of a minoritized group.

I’m less concerned about this as your private opinion voiced publicly than I am about what your legions of followers will think and do after reading it.

There’s already enough horrible misconceptions about disability out there, we don’t need any more. If you’re reaction here is to think, “Well, you’re the one gatekeeping in telling me what I can’t say!” I’d ask you to reread the “But I’m a good person!” section.

I’m not naïve enough to think this will close discussion on the topic, but I do hope this article is something you can send as a reply to the next person who gets all fired up to make this kind of tiresomely pithy observation.

If you’ve been sent this post, why not turn your energies towards something more constructive? Auditing your site for accessibility issues is a good place to start. Even better: use that time to read, and to listen.

Further reading

- In Defense of the a11y Hashtag Customer Servant Consultancy

- a11y = Accessibility Adrian Roselli

- Quick tip: a11y and a brief numeronyms - primer The A11Y Project

- Is ‘a11y’ our ally? - Thoughts on a tag for web accessibility The '58 sound

- Origin Of The Abbreviation I18n I18nGuy